At this point, you should understand how each commit creates an entire new filesystem tree (called a “revision”) in the repository. If not, go back and read about revisions in the section called “Revisions”.

For this chapter, we'll go back to the same example from

Chapter 2. Remember that you and your collaborator, Sally, are

sharing a repository that contains two projects,

paint and calc.

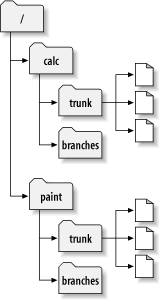

Notice that in Figure 4.2, “Starting repository layout”, however, each

project directory now contains subdirectories named

trunk and branches.

The reason for this will soon become clear.

As before, assume that Sally and you both have working

copies of the “calc” project. Specifically, you

each have a working copy of /calc/trunk.

All the files for the project are in this subdirectory rather

than in /calc itself, because your team has

decided that /calc/trunk is where the

“main line” of development is going to take

place.

Let's say that you've been given the task of performing a

radical reorganization of the project. It will take a long time

to write, and will affect all the files in the project. The

problem here is that you don't want to interfere with Sally, who

is in the process of fixing small bugs here and there. She's

depending on the fact that the latest version of the project (in

/calc/trunk) is always usable. If you

start committing your changes bit-by-bit, you'll surely break

things for Sally.

One strategy is to crawl into a hole: you and Sally can stop

sharing information for a week or two. That is, start gutting

and reorganizing all the files in your working copy, but don't

commit or update until you're completely finished with the task.

There are a number of problems with this, though. First, it's

not very safe. Most people like to save their work to the

repository frequently, should something bad accidentally happen

to their working copy. Second, it's not very flexible. If you

do your work on different computers (perhaps you have a working

copy of /calc/trunk on two different

machines), you'll need to manually copy your changes back and

forth, or just do all the work on a single computer. By that

same token, it's difficult to share your changes-in-progress

with anyone else. A common software development “best

practice” is to allow your peers to review your work as you

go. If nobody sees your intermediate commits, you lose

potential feedback. Finally, when you're finished with all your

changes, you might find it very difficult to re-merge your final

work with the rest of the company's main body of code. Sally

(or others) may have made many other changes in the repository

that are difficult to incorporate into your working

copy—especially if you run svn update

after weeks of isolation.

The better solution is to create your own branch, or line of development, in the repository. This allows you to save your half-broken work frequently without interfering with others, yet you can still selectively share information with your collaborators. You'll see exactly how this works later on.

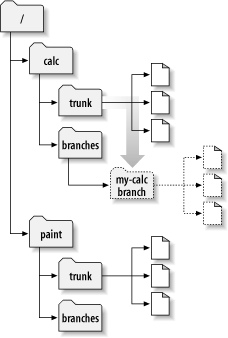

Creating a branch is very simple—you make a copy of

the project in the repository using the svn

copy command. Subversion is not only able to copy

single files, but whole directories as well. In this case,

you want to make a copy of the

/calc/trunk directory. Where should the

new copy live? Wherever you wish—it's a matter of

project policy. Let's say that your team has a policy of

creating branches in the /calc/branches

area of the repository, and you want to name your branch

my-calc-branch. You'll want to create a

new directory,

/calc/branches/my-calc-branch, which

begins its life as a copy of

/calc/trunk.

There are two different ways to make a copy. We'll

demonstrate the messy way first, just to make the concept

clear. To begin, check out a working copy of the project's

root directory, /calc:

$ svn checkout http://svn.example.com/repos/calc bigwc A bigwc/trunk/ A bigwc/trunk/Makefile A bigwc/trunk/integer.c A bigwc/trunk/button.c A bigwc/branches/ Checked out revision 340.

Making a copy is now simply a matter of passing two working-copy paths to the svn copy command:

$ cd bigwc $ svn copy trunk branches/my-calc-branch $ svn status A + branches/my-calc-branch

In this case, the svn copy command

recursively copies the trunk working

directory to a new working directory,

branches/my-calc-branch. As you can see

from the svn status command, the new

directory is now scheduled for addition to the repository.

But also notice the “+” sign next to the letter

A. This indicates that the scheduled addition is a

copy of something, not something new.

When you commit your changes, Subversion will create

/calc/branches/my-calc-branch in the

repository by copying /calc/trunk, rather

than resending all of the working copy data over the

network:

$ svn commit -m "Creating a private branch of /calc/trunk." Adding branches/my-calc-branch Committed revision 341.

And now the easier method of creating a branch, which we should have told you about in the first place: svn copy is able to operate directly on two URLs.

$ svn copy http://svn.example.com/repos/calc/trunk \

http://svn.example.com/repos/calc/branches/my-calc-branch \

-m "Creating a private branch of /calc/trunk."

Committed revision 341.

There's really no difference between these two methods.

Both procedures create a new directory in revision 341, and

the new directory is a copy of

/calc/trunk. This is shown in Figure 4.3, “Repository with new copy”. Notice that the second method,

however, performs an immediate commit.

[8]

It's an easier procedure, because it doesn't require you to

check out a large mirror of the repository. In fact, this

technique doesn't even require you to have a working copy at

all.

Now that you've created a branch of the project, you can check out a new working copy to start using it:

$ svn checkout http://svn.example.com/repos/calc/branches/my-calc-branch A my-calc-branch/Makefile A my-calc-branch/integer.c A my-calc-branch/button.c Checked out revision 341.

There's nothing special about this working copy; it simply

mirrors a different directory in the repository. When you

commit changes, however, Sally won't ever see them when she

updates. Her working copy is of

/calc/trunk. (Be sure to read the section called “Switching a Working Copy” later in this chapter: the

svn switch command is an alternate way of

creating a working copy of a branch.)

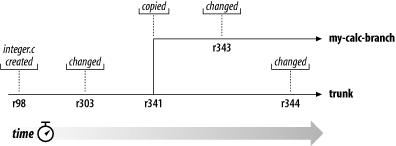

Let's pretend that a week goes by, and the following commits happen:

You make a change to

/calc/branches/my-calc-branch/button.c, which creates revision 342.You make a change to

/calc/branches/my-calc-branch/integer.c, which creates revision 343.Sally makes a change to

/calc/trunk/integer.c, which creates revision 344.

There are now two independent lines of development, shown

in Figure 4.4, “The branching of one file's history”, happening on

integer.c.

Things get interesting when you look at the history of

changes made to your copy of

integer.c:

$ pwd /home/user/my-calc-branch $ svn log --verbose integer.c ------------------------------------------------------------------------ r343 | user | 2002-11-07 15:27:56 -0600 (Thu, 07 Nov 2002) | 2 lines Changed paths: M /calc/branches/my-calc-branch/integer.c * integer.c: frozzled the wazjub. ------------------------------------------------------------------------ r341 | user | 2002-11-03 15:27:56 -0600 (Thu, 07 Nov 2002) | 2 lines Changed paths: A /calc/branches/my-calc-branch (from /calc/trunk:340) Creating a private branch of /calc/trunk. ------------------------------------------------------------------------ r303 | sally | 2002-10-29 21:14:35 -0600 (Tue, 29 Oct 2002) | 2 lines Changed paths: M /calc/trunk/integer.c * integer.c: changed a docstring. ------------------------------------------------------------------------ r98 | sally | 2002-02-22 15:35:29 -0600 (Fri, 22 Feb 2002) | 2 lines Changed paths: M /calc/trunk/integer.c * integer.c: adding this file to the project. ------------------------------------------------------------------------

Notice that Subversion is tracing the history of your

branch's integer.c all the way back

through time, even traversing the point where it was copied.

It shows the creation of the branch as an event in the

history, because integer.c was implicitly

copied when all of /calc/trunk/ was

copied. Now look what happens when Sally runs the same

command on her copy of the file:

$ pwd /home/sally/calc $ svn log --verbose integer.c ------------------------------------------------------------------------ r344 | sally | 2002-11-07 15:27:56 -0600 (Thu, 07 Nov 2002) | 2 lines Changed paths: M /calc/trunk/integer.c * integer.c: fix a bunch of spelling errors. ------------------------------------------------------------------------ r303 | sally | 2002-10-29 21:14:35 -0600 (Tue, 29 Oct 2002) | 2 lines Changed paths: M /calc/trunk/integer.c * integer.c: changed a docstring. ------------------------------------------------------------------------ r98 | sally | 2002-02-22 15:35:29 -0600 (Fri, 22 Feb 2002) | 2 lines Changed paths: M /calc/trunk/integer.c * integer.c: adding this file to the project. ------------------------------------------------------------------------

Sally sees her own revision 344 change, but not the change you made in revision 343. As far as Subversion is concerned, these two commits affected different files in different repository locations. However, Subversion does show that the two files share a common history. Before the branch-copy was made in revision 341, they used to be the same file. That's why you and Sally both see the changes made in revisions 303 and 98.

There are two important lessons that you should remember from this section.

Unlike many other version control systems, Subversion's branches exist as normal filesystem directories in the repository, not in an extra dimension. These directories just happen to carry some extra historical information.

Subversion has no internal concept of a branch—only copies. When you copy a directory, the resulting directory is only a “branch” because you attach that meaning to it. You may think of the directory differently, or treat it differently, but to Subversion it's just an ordinary directory that happens to have been created by copying.

[8] Subversion does not support cross-repository copying. When using URLs with svn copy or svn move, you can only copy items within the same repository.